Read time: 8 minutes

When you can't catch your breath, your body doesn't ask permission to adapt.

It recruits backup. It pulls in help from muscles that were never meant to breathe full-time. And for people living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), this adaptation becomes a daily reality.

This is accessory muscle breathing, when your neck, shoulders, and upper chest take over the work your diaphragm can no longer handle alone.

If you've noticed your shoulders rising with every breath, or if someone you care for shows visible strain in their neck while breathing, you're witnessing your body's emergency response system working overtime.

Here's what's actually happening inside your respiratory system, and what you can do about it.

In this article, you'll discover:

- What accessory muscle breathing is and why it occurs in COPD

- The specific muscles involved and their normal versus compensatory roles

- How hyperinflation and air trapping trigger accessory muscle recruitment

- Physical signs that indicate accessory breathing patterns

- Evidence, based breathing techniques that reduce accessory muscle load

- Posture adjustments that support more efficient breathing mechanics

- When accessory muscle use signals a medical emergency

Table of Contents

──────────────

What Is Accessory Muscle Breathing?

Why Accessory Breathing Happens in COPD

What Accessory Breathing Looks Like

When Accessory Breathing Signals Emergency

Evidence-Based Strategies to Support Breathing

- Pursed-Lip Breathing

- Diaphragmatic Breathing Retraining

- Positional Strategies

The Role of Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Understanding the Adaptation

Key Takeaways: Supporting Breath in COPD

Frequently Asked Questions About Accessory Breathing in COPD

Related Articles

References

──────────────

What Is Accessory Muscle Breathing?

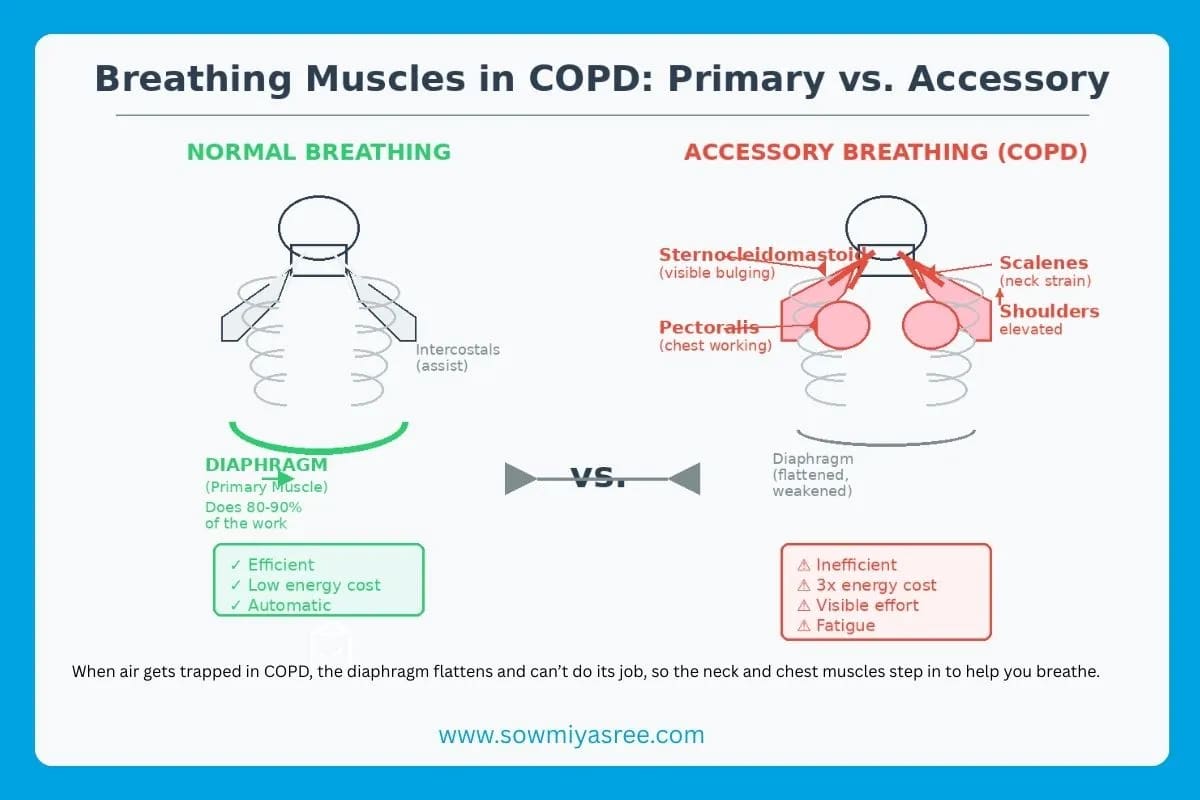

In healthy, efficient breathing, your diaphragm does approximately 80% of the respiratory work.¹

It contracts downward, creating negative pressure that draws air into your lungs. It relaxes, and air flows out. The external intercostal muscles between your ribs assist with chest expansion, but the diaphragm carries the primary load.

Minimal effort. Minimal energy. Maximum efficiency.

You shouldn't need to see breathing happening.

Accessory muscle breathing occurs when this primary system can't keep up with ventilatory demands. The body activates secondary respiratory muscles, the sternocleidomastoid in your neck, the scalenes connecting your neck to your upper ribs, and the pectoralis major and minor in your chest.²

These muscles are designed for emergencies: sprinting to catch a bus, climbing steep stairs, moments of acute respiratory distress.

When they activate regularly, especially during rest, breathing shifts from an automatic background function to visible, effortful work.

Why Accessory Breathing Happens in COPD

COPD fundamentally alters respiratory mechanics.

In healthy lungs, air flows in and out efficiently. But in COPD, chronic inflammation narrows airways and destroys alveolar walls, creating two critical problems:

1. Air trapping Damaged airways collapse during exhalation, trapping air inside the lungs. This residual air accumulates with each breath.³

2. Hyperinflation The trapped air forces the lungs to expand beyond their optimal volume. The chest barrel-shapes. The diaphragm flattens.⁴ Imagine trying to breathe with a balloon already half full.

Here's where the mechanical problem becomes critical: a flattened diaphragm loses its dome shape and, with it, its mechanical advantage for generating inspiratory pressure.⁴

Research shows that in COPD, the diaphragm and intercostal muscles face increased load due to elevated lung resistance and elastance, while simultaneously losing their capacity to generate adequate pressure due to hyperinflation.⁴

The body compensates by recruiting accessory muscles.

Not because it wants to. Because it has to survive.

Studies using surface electromyography confirm that patients with COPD show significantly increased activity in the scalene, sternocleidomastoid, and pectoralis major muscles during both quiet breathing and pursed-lip breathing compared to healthy individuals.²

The Energy Cost of Compensation

This compensation isn't free.

Accessory muscle breathing costs significantly more energy than diaphragmatic breathing, some estimates suggest up to three times the metabolic expenditure.⁵ This is why a shower can feel like a workout.

Your respiratory system is running in first gear, burning fuel at an accelerated rate just to maintain basic ventilation.

This helps explain why COPD patients often experience:

- Chronic fatigue unrelated to activity level

- Shortness of breath during minimal exertion

- Persistent neck and shoulder tension

- Reduced capacity for sustained physical activity

The muscles recruited for emergency breathing aren't built for marathon endurance. They fatigue. They ache. And the cycle perpetuates.

What Accessory Breathing Looks Like

Clinical observation of breathing patterns provides critical diagnostic information.

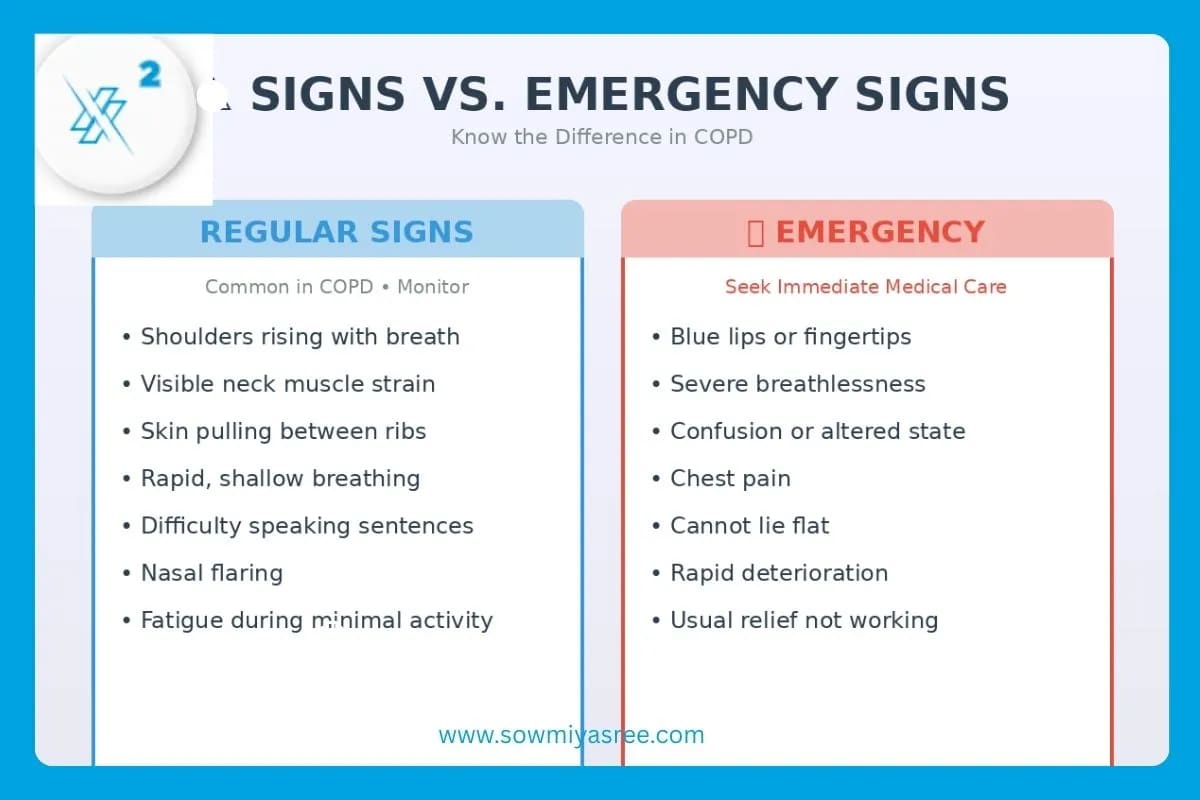

Physical signs of accessory muscle use include:

- Visible shoulder elevation with each inhalation

- Neck muscle bulging or straining (sternocleidomastoid and scalenes)

- Suprasternal and intercostal retractions (skin pulling inward at the neck and between ribs)

- Rapid, shallow breathing pattern (increased respiratory rate with reduced tidal volume)

- Nasal flaring during inhalation

- Difficulty speaking in complete sentences without pausing for breath

In COPD patients, the frequency and intensity of accessory muscle use, particularly during rest, can indicate disease severity and progression.⁶

Clinicians assess not just how fast someone breathes, but how they breathe. The quality of the breathing pattern reveals the work being performed behind the scenes.

When Accessory Breathing Signals Emergency

While chronic accessory muscle use is common in COPD, certain presentations require immediate medical attention.

Seek emergency care if accessory muscle breathing occurs alongside:

- Cyanosis (bluish discoloration of lips, fingertips, or skin)

- Severe breathlessness that prevents speaking

- Confusion or altered mental status

- Chest pain

- Inability to lie flat without severe respiratory distress

- Rapid deterioration in breathing capacity

These signs may indicate acute exacerbation of COPD, respiratory failure, or other life-threatening complications that require urgent intervention beyond breathing techniques.

Evidence-Based Strategies to Support Breathing

While breathing techniques cannot reverse COPD, they can reduce the mechanical load on accessory muscles and improve ventilatory efficiency.

1. Pursed-Lip Breathing

Research demonstrates that pursed-lip breathing significantly increases tidal volume and decreases respiratory rate in COPD patients.²

How it works:

- Inhale slowly through your nose for 2 counts

- Exhale slowly through pursed lips (as if blowing out a candle) for 4-6 counts

- The prolonged exhalation creates positive pressure in the airways, preventing premature airway collapse

- This reduces air trapping and allows more complete lung emptying

Why it helps: By maintaining airway patency during exhalation, pursed-lip breathing reduces the need to forcefully recruit accessory muscles for the next inhalation. Studies using electromyography show this technique increases scalene and sternocleidomastoid muscle activity during practice, which paradoxically helps retrain breathing patterns over time.²

2. Diaphragmatic Breathing Retraining

Although the diaphragm in COPD operates at a mechanical disadvantage, targeted practice can optimize its remaining function.

Technique:

- Lie in a comfortable position or sit with back support

- Place one hand on your chest, one on your abdomen

- Breathe slowly through your nose, focusing on expanding the abdomen while minimizing chest movement

- Exhale slowly and completely

- Practice 5-10 minutes, 2-3 times daily

The goal: Not to eliminate accessory muscle use entirely, that may not be possible in moderate to severe COPD, but to reduce unnecessary recruitment and improve coordination between diaphragm and accessory muscles.

3. Positional Strategies

Body position significantly affects respiratory mechanics.

The forward-leaning position with arm support is commonly adopted by COPD patients during dyspnea because it mechanically stabilizes the shoulder girdle, allowing accessory muscles to work more efficiently.²

Research comparing different sitting postures found that positions with arm support (hands on knees, elbows on table) increased inspiratory accessory muscle activity compared to neutral sitting, but this increased activity occurred in a mechanically advantaged position that many patients find reduces breathlessness.²

Practical applications:

- When breathless, lean forward with forearms resting on a table or knees

- This "tripod position" is not a failure, it's biomechanically sound support

- Use it during exacerbations or when recovering from exertion

The Role of Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Structured pulmonary rehabilitation programs demonstrate consistent improvements in respiratory muscle strength, exercise tolerance, and quality of life for COPD patients.⁷

These programs typically combine:

- Inspiratory muscle training to strengthen respiratory muscles

- Exercise conditioning to improve overall cardiopulmonary fitness

- Breathing technique education for practical application

- Energy conservation strategies to reduce ventilatory demand

A meta-analysis of breathing exercises in COPD found significant improvements in maximum inspiratory pressure (PImax) and six-minute walk distance when patients engaged in structured respiratory training programs.⁸

The improvements arise not just from diaphragm strengthening, but from enhanced coordination between all respiratory muscles, including more efficient recruitment patterns of accessory muscles.

Understanding the Adaptation

Here's what's crucial to understand: accessory muscle breathing in COPD is not a personal failure or a bad habit.

It's an intelligent physiological adaptation to mechanical constraints.

Your body is working with compromised equipment, narrowed airways, trapped air, a flattened diaphragm, and it's recruiting additional resources to maintain gas exchange and keep you alive.

The clinical challenge isn't to eliminate accessory muscle use. In moderate to severe COPD, that may be neither possible nor desirable.

The goal is to optimize the pattern. To reduce unnecessary energy expenditure. To coordinate the respiratory muscles so they work together rather than fighting against mechanical disadvantages.

Breathing doesn't suddenly fail in COPD. It adapts, compensates, recruits help.

Accessory muscle breathing is your body saying: "I'm managing but I'm working harder than I should have to."

And learning to recognize that signal is the first step toward supporting your respiratory system more intelligently.

Key Takeaways: Supporting Breath in COPD

✓ Accessory muscle breathing is compensation, not failure – Your body recruits neck and shoulder muscles when the diaphragm can't meet ventilatory demands alone

✓ Hyperinflation is the mechanical trigger – Air trapping flattens the diaphragm, reducing its force-generating capacity and necessitating accessory muscle recruitment

✓ The energy cost is significant – Accessory breathing requires substantially more metabolic energy than diaphragmatic breathing, contributing to chronic fatigue

✓ Breathing techniques can help – Pursed-lip breathing, diaphragmatic training, and positional strategies reduce mechanical load on accessory muscles

✓ Forward-leaning positions are biomechanically sound – Arm-supported postures aren't signs of weakness; they mechanically optimize accessory muscle function

✓ Pulmonary rehabilitation shows evidence – Structured programs improve respiratory muscle coordination, strength, and breathing efficiency

✓ Emergency signs require immediate care – Cyanosis, severe dyspnea, confusion, or chest pain alongside accessory breathing signals acute crisis

Frequently Asked Questions About Accessory Breathing in COPD

Q: Is accessory muscle breathing always bad?

No. During exercise or increased ventilatory demand, even healthy individuals recruit accessory muscles. The concern in COPD is when these muscles activate during rest or minimal activity, indicating the primary respiratory muscles can't handle baseline demands.

Q: Can I stop using accessory muscles if I practice enough?

In mild COPD, breathing retraining may significantly reduce accessory muscle reliance. In moderate to severe disease, complete elimination may not be realistic. The goal is optimization, using these muscles more efficiently, not eliminating their contribution entirely.

Q: Why does leaning forward help my breathing?

The forward-leaning position with arm support stabilizes your shoulder girdle, creating a fixed point from which accessory muscles can pull more effectively. It's biomechanically advantageous and explains why many COPD patients instinctively adopt this posture during breathlessness.

Q: How long does it take to retrain breathing patterns?

Research on breathing interventions typically shows measurable improvements in 4-8 weeks with consistent daily practice. However, breathing pattern modification requires ongoing attention, particularly during exacerbations when old patterns tend to resurface.

Q: Will breathing exercises cure my COPD?

No. Breathing exercises cannot reverse airway damage or restore lost lung function. They can, however, improve respiratory muscle efficiency, reduce symptom burden, enhance exercise tolerance, and improve quality of life within the constraints of the disease.

Q: When should I be worried about my breathing pattern?

Regular accessory muscle use is expected in COPD. Worry when you notice sudden changes, dramatically increased work of breathing at rest, inability to speak, confusion, or cyanosis. These require immediate medical evaluation.

Related Articles:

──────────────

- The Breath-Energy Connection: Powerful Ways to Boost Your Natural Vitality

- The Hidden Science of Nostril Breathing: How Your Nose Controls Your Brain Function

- How Long Should Your Breathing Sessions Be? What This Neuroscientist Discovered Will Shock You

──────────────

References

- Koulouris, N. G., & Hardavella, G. (2011). Physiological techniques for detecting expiratory flow limitation during tidal breathing. European Respiratory Review, 20(121), 203–213. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21881143/

- Kim, K.-S., Byun, M.-K., Lee, W.-H., Cynn, H.-S., Kwon, O.-Y., & Oh, J.-S. (2012). Effects of breathing maneuver and sitting posture on muscle activity in inspiratory accessory muscles in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine, 7(1), Article 9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22958459/

- Seladi-Schulman, J. (2022, September 5). Accessory muscle breathing: In infants, end of life, and more. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/accessory-muscle-breathing

- Klimathianaki, M., Vassilakopoulos, T., & Petrof, B. J. (2011). Respiratory muscle dysfunction in COPD: From muscles to cell. European Respiratory Review, 20(119), 23–33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21194407/

- Khokhar, O. (2024). Accessory muscle breathing: What it is and why it matters in COPD. HealthCentral. https://www.healthcentral.com/condition/copd/accessory-muscle-breathing

- Ferreira, J. G., Coelho, C. C., Gomes, R. S., de Almeida Brito, E., & Neder, J. A. (2024). Differences of ventilatory muscle recruitment and work of breathing in COPD and interstitial lung disease during exercise: A comprehensive evaluation. ERJ Open Research, 10(4), Article 00059-2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38978542/

- Gosselink, R., De Vos, J., van den Heuvel, S. P., Segers, J., Decramer, M., & Kwakkel, G. (2011). Impact of inspiratory muscle training in patients with COPD: What is the evidence? A systematic review. European Respiratory Journal, 37(2), 416–425. https://research.vu.nl/en/publications/impact-of-inspiratory-muscle-training-in-patients-with-copd-what-/

- Li, P., Liu, J., Lu, Y., Liu, X., & Wang, X. (2018). Effects of long-term home-based Liuzijue exercise combined with clinical guidance in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 13, 1501–1509. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6080664/

About the Author

Sowmiya Sree is a breathwork researcher and author specializing in the intersection of ancient breathing practices and modern neuroscience. Her work focuses on making breath science accessible and actionable for individuals managing chronic conditions, stress, and emotional regulation challenges.

Xpand Your Breath, Xpand Your Life

BreathX²

Medical Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. COPD is a serious medical condition requiring professional diagnosis and treatment. Always consult with qualified healthcare providers regarding your respiratory health and before implementing new breathing techniques or exercises.