I stepped outside this morning, and immediately when I exhaled, small clouds of vapor rose into the cold air.

It's always fun to watch that, isn't it? There's something almost magical about seeing your breath materialize in front of you, a reminder that winter has truly arrived.

We've all seen those vapor clouds since childhood. We've made dragon breath jokes, tried to blow the biggest clouds, and watched them dissipate into the morning air. But here's what nobody tells you about visible breath:

It's not just condensation. It's water leaving your body.

Every visible exhale represents moisture you need to replace. And most people have no idea how much hydration they're losing just by breathing in winter air.

That scratchy throat that won't go away?

The persistent dry cough that makes people ask if you're sick?

The sinuses that feel like sandpaper by midday?

That's often not a cold coming on; that's your airways literally crying out for water.

And that visible cloud you see with every breath? It's your body showing you exactly what's happening in real-time.

Quick 5-Point Summary

- That winter breath cloud is water leaving your body, most people don't realize how much they're dehydrating just by breathing in cold air

- Your body heats and humidifies every breath 20,000+ times daily, pulling moisture from your airways and causing that scratchy throat feeling

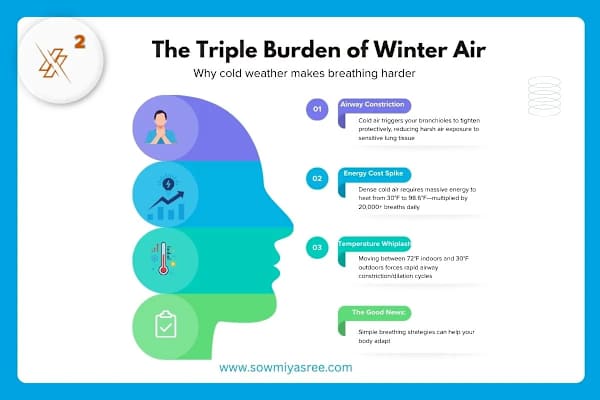

- Cold air makes breathing harder in three ways: airways constrict, energy costs spike, and rapid indoor-outdoor temperature changes stress your system

- Your nose warms air by 20-30°F before it reaches your lungs, but most people unconsciously switch to mouth breathing in winter, losing this protection

- Simple fixes work: track visible breath as your hydration signal, use a scarf to buffer cold air, slow your inhales, and keep indoor humidity at 40-50%

Table of Contents

──────────────

Why Winter Breathing Dehydrates You

What Else Winter Does to Your Breathing

Five Evidence-Based Strategies to Breathe Easier All Winter

The 'Doorway Pause' Technique.

Your Winter Breath Awareness Challenge

The Bottom Line on Winter Breathing

Want to Go Deeper?

References

Why Winter Breathing Dehydrates You (Even When You Think You're Drinking Enough Water)

Here's what's actually happening inside your respiratory system when temperatures drop:

Your lungs need to operate at nearly 100% humidity and 98.6°F (37°C). Always. Summer or winter. There's no seasonal variation your lungs can tolerate; they need tropical conditions 24/7.¹

When you inhale cold, dry winter air, your body has to:

- Heat it by 20-30°F (11-17°C) before it reaches your lungs

- Humidify it to nearly 100% relative humidity

- Do this 17,000-25,000 times per day²

Where does that moisture come from?

Your body's water reserves are pulled directly from the mucous membranes lining your entire respiratory tract, from your nose down to your bronchioles.

Every. Single. Breath.

In the summer, outdoor air is already somewhat warm and humid (typically 50-80% humidity), so your body doesn't have to work as hard. In winter, especially with indoor heating running constantly, the air can have as little as 10-20% relative humidity, drier than some deserts.³

Your body is essentially running a 24/7 humidification system, and most of us aren't replacing the water it's using.

The rule most people miss: If you can see your breath, you need to be drinking significantly more water than you think.

What Else Winter Does to Your Breathing (And Why the Same Walk Feels Exhausting)

The dehydration is just the beginning. Winter changes your breathing in three other major ways that most people never connect to the season:

1. Your Airways Constrict Protectively

Cold air triggers your bronchioles (the small airways in your lungs) to tighten slightly.⁴ This is your body's protective mechanism; by narrowing the airways, you reduce the volume of harsh, cold air hitting sensitive lung tissue at once.

Brilliant design, except it makes breathing feel more labored, especially during any kind of movement. That tightness you feel in your chest when you first step outside? That's bronchoconstriction in action.

For people with asthma or exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, this winter airway tightening can be particularly challenging. Cold air is one of the most common asthma triggers.⁵

2. The Energy Cost of Breathing Spikes Dramatically

Here's the counterintuitive part: cold air is actually denser than warm air, which means there are more oxygen molecules packed into each breath.⁶

Sounds like a good thing, right? More oxygen should mean easier breathing.

Except your body has to work significantly harder to warm and process that dense, cold air. The energy expenditure required to heat each breath from 30°F to 98.6°F, multiplied by 20,000+ breaths per day, adds up to a substantial metabolic cost.⁷

This is why the same walk that feels easy in July leaves you winded in December. You're not out of shape. Your respiratory system is just working overtime behind the scenes.

3. Temperature Whiplash Stresses Your System

This one might be the most overlooked factor: the constant transitions between indoor and outdoor environments.

Moving from 72°F indoors to 30°F outdoors, and back again, multiple times daily, forces your airways to rapidly constrict and dilate, constrict and dilate, over and over.⁸

This constant adaptation is actually harder on your respiratory system than consistently cold air would be. It's like forcing your airways to do interval training all day without rest.

This temperature whiplash explains why many people experience persistent throat irritation throughout winter, even when they're not actually sick. The irritation isn't from a virus; it's from the repeated stress of temperature adaptation.

Five Evidence-Based Strategies to Breathe Easier All Winter

Now that you understand what's happening, here's how to work with your body instead of against it:

1. Track Your Visible Exhales as a Hydration Cue

Use that vapor cloud as real-time biofeedback. The more visible your breath (indicating colder, drier air), the more aggressively you need to hydrate.

On extremely cold days when you can see your breath with every exhale, aim for more water intake than normal. This isn't just about drinking more; it's about replacing what you're visibly losing.

Keep a water bottle with you and take a drink every time you notice your breath clouds are particularly dense.

2. Create a Microclimate with a Scarf (The Science Behind This Old Trick)

Wrapping a scarf loosely over your nose and mouth isn't just about warmth; it's about creating a pocket of conditioned air.

Here's what happens: every exhale releases warm (98.6°F), humid (100% relative humidity) air. The scarf traps this air briefly, creating a buffer zone. Your next inhale pulls from that pocket of air you just warmed and moistened.⁹

You're essentially pre-conditioning the air before it even enters your nose, reducing the work your respiratory system has to do.

Key: keep the scarf loose. You want air circulation, just with a conditioning buffer. Too tight defeats the purpose and can make breathing feel restricted.

3. Slow Your Inhale Speed to Allow Proper Warming

Most people's instinctive response to cold air is quick, gasping breaths. This feels easier in the moment, but actually makes things worse.

Try this instead: inhale slowly and steadily for 4-5 counts through your nose. This extended inhale time gives your nasal passages the seconds they need to properly warm and humidify the air before it reaches your lungs.

The slower the inhale, the less shock your system experiences. Think of it like slowly lowering yourself into a cold pool versus jumping in, same destination, vastly different experience for your body.

4. Humidify Indoor Spaces (Especially Your Bedroom)

Indoor heating systems dramatically reduce relative humidity, often dropping it to 10-20% levels found in arid deserts.¹⁰ Your respiratory system is trying to humidify this bone-dry air all night while you sleep.

A humidifier in your bedroom (aim for 40-50% relative humidity) dramatically reduces the work your respiratory system has to do during those 7-8 hours of sleep.

This single intervention often resolves morning throat scratchiness and that annoying dry cough that seems to appear every winter.

5. Use Nasal Breathing When Possible (Your Built-In HVAC System)

Your nose is essentially a biological heating, ventilation, and air conditioning system.

The nasal passages contain turbinates—scroll-shaped structures covered in blood vessels that act like radiators, warming incoming air by 20-30°F before it reaches your throat.¹¹ They also humidify the air and filter out particles.

Additionally, nasal breathing triggers the release of nitric oxide, a molecule that helps dilate blood vessels and actually counteracts the cold-induced airway constriction.¹²

I know nose breathing doesn't always feel comfortable in extreme cold. If it feels too restrictive, try this hybrid approach: inhale through your nose (warming and filtering), exhale through pursed lips (releasing pressure). You get the benefits on the inhale without the discomfort on the exhale.

The 'Doorway Pause' Technique

Here's a simple technique that makes a surprising difference:

Before stepping outside into cold air, pause. Take 30 seconds to breathe slowly and deeply through your nose while still indoors. This primes your respiratory system; it's like a warm-up for your airways.

Your body starts activating the warming and humidification systems in anticipation, so the temperature shock is less severe when you actually step out.

Do the same when returning inside. Don't immediately jump back into activity or conversation. Give your airways 30 seconds to adjust to the warmer, drier indoor air.

This buffer period—just one minute total per transition-can prevent much of that persistent throat irritation that plagues people all winter.

Your Winter Breath Awareness Challenge

This week, I want you to become a breath detective. Just notice:

- When can you see your breath? Is it only outdoors, or also in your car before it warms up? In your garage? In certain rooms of your house?

- How often are you actually drinking water on those days? Track it. You might be surprised at the gap between what you think you're drinking and reality.

- Are you taking shorter, shallower breaths without realizing it? Many people unconsciously shift to rapid, shallow breathing in cold weather, exactly the opposite of what helps.

Winter isn't making you breathe wrong. It's revealing breathing patterns you might not notice in easier conditions.

And that visible cloud with every exhale? It's not just physics. It's your body asking for awareness—and a little care.

The Bottom Line on Winter Breathing

Those vapor clouds you've been watching since childhood are actually one of the few times your breath becomes visible feedback. Your body is showing you, in real-time, that you're losing moisture with every exhale.

The scratchy throat, the persistent cough, the feeling that breathing is harder, these aren't inevitable winter experiences. They're signals that your respiratory system needs support.

The strategies above aren't about fighting winter. They're about working with the season, understanding what your body is doing, and giving it the conditions it needs to breathe efficiently, even when the air is harsh.

Because breathing easier isn't just about comfort. When your respiratory system isn't struggling, you have more energy for everything else. You sleep better. You move more easily. You get sick less often.

All from paying attention to something you do 20,000 times a day without thinking about it.

So the next time you step outside and see that cloud of vapor rise from your lips, don't just think "it's cold out."

Think: "My body is asking for water."

And then do something about it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why does my throat feel dry all winter, even when I drink water?

A: You're losing moisture with every breath. Cold air has 10-20% humidity, and your body pulls water from your airways to humidify it to 100% before it reaches your lungs, up to 25,000 times daily. Drink more water than your normal water intake when you can see your breath.

Q: Is it better to breathe through my nose or mouth in cold weather?

A: Nose breathing when possible. Your nose warms incoming air by 20-30°F and adds moisture before it hits your lungs. Mouth breathing sends cold, dry air straight to your airways, causing irritation and that burning chest feeling.

Q: Why does the same walk feel harder in winter than summer?

A: Cold air is denser, so your body works overtime to warm and process each breath. The energy cost of heating air from 30°F to 98.6°F, multiplied by 20,000+ breaths, adds significant metabolic demand. You're not out of shape; your respiratory system is just working harder.

Q: Does wearing a scarf over my face actually help?

A: Yes. A scarf traps warm, humid air from your exhales, creating a buffer zone. Your next inhale pulls from that pre-warmed pocket instead of harsh, cold air. Keep it loose for air circulation; you're creating a conditioning zone, not blocking airflow.

Q: Should I be worried about those vapor clouds when I breathe out?

A: Not worried, but aware. Visible breath is real-time feedback that you're losing water. The bigger and more frequent the clouds, the more aggressively you need to hydrate. It's your body's way of showing you exactly what's happening with each exhale.

Want to Go Deeper?

──────────────

Nose Breathing vs Mouth Breathing: Why Your Breathing Technique Matters

What Does Shortness of Breath on Stairs Mean?

The 4-Step Altitude Breathing Method That Transforms Mountain Adventures

──────────────

References:

- Keck, T., Leiacker, R., Heinrich, A., Kühnemann, S., & Rettinger, G. (2000). Humidity and temperature profile in the nasal cavity. Rhinology, 38(4), 167–171. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11190750/

- Guyton, A. C., & Hall, J. E. (2015). Textbook of medical physiology (13th ed.). Elsevier.

- Wolkoff, P. (2018). Indoor air humidity, air quality, and health—An overview. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 221(3), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.01.015

- Koskela, H. O. (2007). Cold air-provoked respiratory symptoms: The mechanisms and management. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 66(2), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v66i2.18237

- D'Amato, M., Molino, A., Calabrese, G., Cecchi, L., Annesi-Maesano, I., & D'Amato, G. (2018). The impact of cold on the respiratory tract and its consequences to respiratory health. Clinical and Translational Allergy, 8, Article 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13601-018-0208-9

- McFadden, E. R., Jr., Pichurko, B. M., Bowman, H. F., Ingenito, E., Burns, S., Dowling, N., & Solway, J. (1985). Thermal mapping of the airways in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology, 58(2), 564-570. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1985.58.2.564

- McFadden, E. R., Jr. (1983). Respiratory heat and water exchange: Physiological and clinical implications. Journal of Applied Physiology, 54(2), 331–336. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1983.54.2.331

- Larsson, K., Ohlsén, P., Larsson, L., Malmberg, P., Rydström, P. O., & Ulriksen, H. (1993). High prevalence of asthma in cross country skiers. BMJ, 307(6915), 1326–1329. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.307.6915.1326

- Millqvist, E., Bengtsson, U., & Löwhagen, O. (1995). Prevention of asthma induced by cold air by cellulose-fabric face mask. Allergy, 50(3), 221–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.1995.tb01137.x

- Arundel, A. V., Sterling, E. M., Biggin, J. H., & Sterling, T. D. (1986). Indirect health effects of relative humidity in indoor environments. Environmental Health Perspectives, 65, 351–361. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1474709/

- Lindemann, J., Leiacker, R., Rettinger, G., & Keck, T. (2002). Nasal mucosal temperature during respiration. Clinical Otolaryngology & Allied Sciences, 27(3), 135–139. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2273.2002.00544.x

- Lundberg, J. O., Weitzberg, E., Lundberg, J. M., & Alving, K. (1996). Nitric oxide in exhaled air. European Respiratory Journal, 9(12), 2671–2680. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.96.09122671

Written by Sowmiya Sree | a Breath Researcher & Author on a series of topics related to Breath

This article is thoroughly researched and fact-checked using peer-reviewed studies and trusted medical resources. Last updated: December 2025

Note: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult your healthcare provider for medical concerns.

Photo by @poiarkovaalfira on Canva